Keith Brazendale, assistant professor in Health Sciences, studies obesity in children, particularly how daily “routine” and “structure” can impact healthy weight in kids. It’s a passion he always had but took time to realize.

He started college as a finance and accounting major. Although he found success in his studies, he was left questioning how he was going to balance this type of work with finding fulfillment and meaning in everyday life.

“I love numbers,” Brazendale says, “But I couldn’t do it the rest of my life.”

Born and raised in Scotland, Brazendale was attending the University of Edinburgh when he decided to switch majors to physical education. He had been an athlete most of his life and found consistent joy in sports and just being physically active with others.

After graduating, he taught secondary school and coached on the side for a while. Although he enjoyed this work, he knew he was destined for higher education.

“I like teaching, and especially the element of passing on knowledge,” Brazendale says.

When he moved to Florida, he enrolled in a master’s program in exercise physiology at Florida Atlantic University to expand his knowledge about human performance.

“It was interesting, because it was kind of the next level of what goes on in the human body during exercise,” Brazendale says. It was there that he had his first taste of conducting research.

His master’s thesis examining the relationship between perceived competence and enjoyment of sport was based on an idea he had while teaching children in Scotland.

“I wanted to know why some children enjoyed it, while other children hated it. Some were good at what they were doing. I thought that it could be related to their experience in PE. If that experience wasn’t a good one for them, maybe, they’re not seeking out additional experiences to be active when they’re away from school.”

Turns out, his hypothesis was incorrect. There was little to no connection to a child’s experience in PE and their future enjoyment of sports. This finding left Brazendale questioning even more how to encourage physical activity among children to set them up for a lifetime of wellness.

Brazendale’s department chair took note of his passion for research and suggested that he apply to a doctoral program in the Arnold School of Public Health at the University of South Carolina.

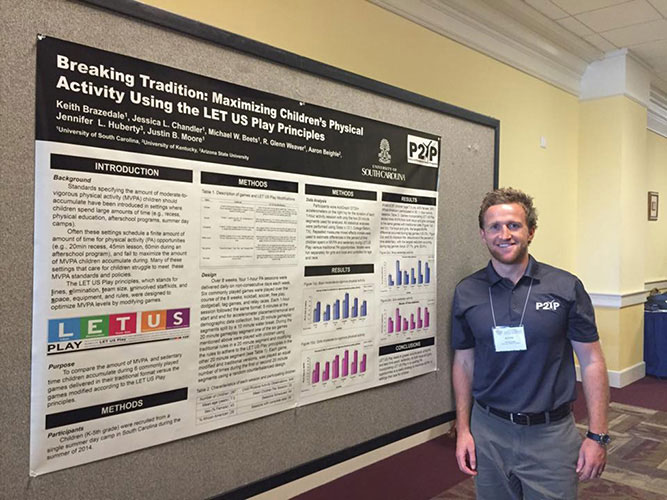

As soon as he arrived, Brazendale threw himself into research. Under the guidance of his mentor, Michael Beets, he worked with an NIH-funded research group called, “Policy to Practice in Youth Programs,” which aimed to get all children active. There, Brazendale and the rest of the team worked closely with after-school programs and day camps, conducting evaluations on the nutrition and activity levels of the attendees. The research team also provided training on new interventions to use in these programs.

His doctoral thesis, “Children’s obesogenic behaviors during summer versus school,” showed preliminary evidence of differences in children’s obesogenic behaviors during summer break versus the school year, and how these behaviors impacted the children’s health outcomes. His data supported the need for new programs that would curtail these unhealthy behaviors that many children were engaging in during summer.

The experience inspired him and his wife to co-found Camp MATES, a nonprofit camp that provided healthy meals and many opportunities for physical activity for children in the summer. Over the course of five summers, the camp grew from 20 attendees to over 100, and each camper attended at a substantially reduced rate thanks to community donations.

“We were very proud of Camp MATES,” Brazendale said. But when the opportunity to work at UCF became available, he couldn’t pass it up.

“UCF empowered me to go out on my own as a researcher,” Brazendale says.

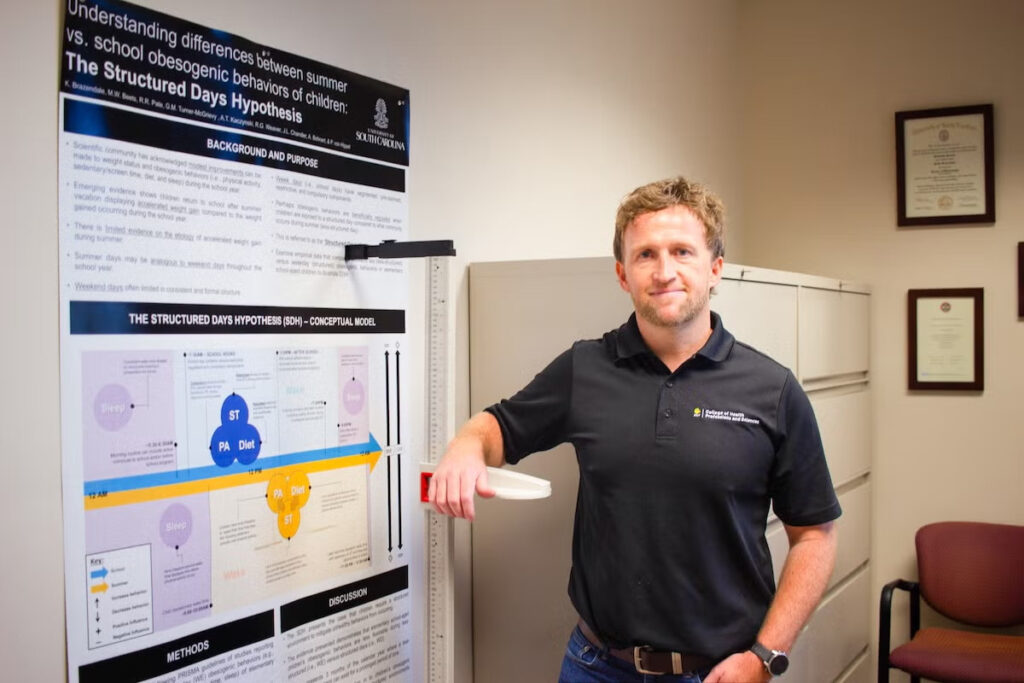

He started working right away on developing and testing his ‘Structured Day Hypothesis’ – a question he had developed over the years in working with kids at summer camps.

“We worked with so many summer programs and we found our efforts to intervene helped, but we only moved the needle a small amount through this approach,” Brazendale says. “Given that, I shifted my research to focus on the longer portion of the year, when kids are in school and have more structure in their schedules.”

With a better understanding of weight gain during the school year in comparison to over the summer, he is able to develop interventions to help decrease risks of childhood obesity. Another goal of his is to get more children from at-risk populations, including minorities, involved in these long-term structured programs to increase lifelong healthy habits to help combat health disparities.

He has been researching this topic since joining UCF in 2019. Little did Brazendale know, but the pandemic would provide him with a novel test group. He had just collected baseline data with schoolchildren in Paisley, FL, eight days before schools went virtual due to COVID-19.

Without attending in-person school, these children unexpectedly were thrust into conditions similar to summer break — with variable sleep and wake times, lunch and breakfast being provided at home in addition to dinner, and no scheduled PE or recess. This participant group was unique in that Brazendale was able to study these children for five months – the longest period of time he has been able to follow participants in his investigations. His findings reaffirmed his hypothesis.

“What I found was that these children gained a significant amount of weight above what you would expect to see as typical growth. This extended ‘less-structured’ time, definitely impacted weight gain and was similar to or even greater than what you might see after summer break,” he said.

These findings support the need for more structure in children’s schedules year-round. Brazendale hopes to partner with schools and community organizations to work toward developing evidence-based programs to support healthy living for children across communities.

In addition to his ongoing research, Brazendale also enjoys introducing undergraduate students to the joy of research through his Applied Research Methodology class, where undergraduate students often get their first taste of research.

Brazendale enjoys inspiring the next generation of researchers and collaborating with them. He currently is mentoring seven students who assist him with primary data collection.

-

Jennifer Kent-Walsh

“Dr. Brazendale’s passion for mentoring students and involving them in his applied research provide invaluable opportunities for undergraduate students in Health Sciences to gain experience in primary data collection, says Jennifer Kent-Walsh, associate dean of research for the College of Health Professions and Sciences. “Such experiences are often the key to igniting a passion for conducting independent research for students – particularly with the immediate human impact of Dr. Brazendale’s work. We are fortunate to have Dr. Brazendale in the College of Health Professions and Sciences at UCF and look forward to the far-reaching impact his research will continue to have on his field and children in our communities.”