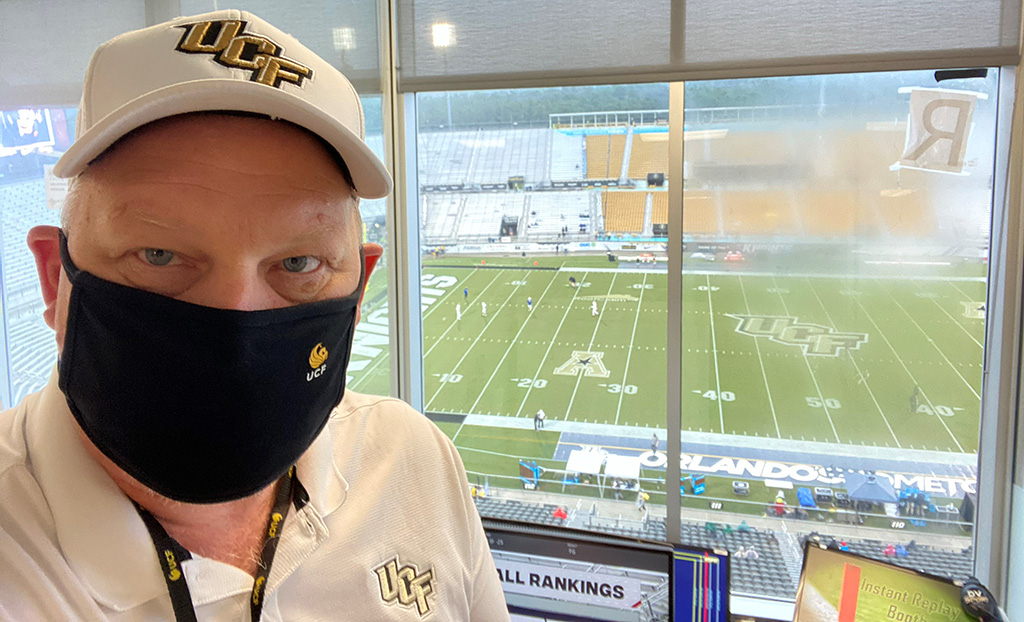

From a vantage point up high in the Bounce House, Christopher Ingersoll, dean of the College of Health Professions and Sciences, will use his expertise in athletic training and care of athletes to scan for possible injuries on the field. This role of medical observer was assigned by the American Athletic Conference for all games played at UCF this football season. Medical Observers in the AAC must be either a licensed and certified athletic trainer or a physician.

In this role, Ingersoll is a neutral observer. He will draw from his experience as a licensed and certified athletic trainer, and researcher in sports medicine and neuroscience, to spot possible injuries in all athletes on the field.

From up high in the sky box, Ingersoll will provide an additional set of eyes on student-athletes to spot injuries that might not be discernible by staff on the sidelines.

“It’s pretty rare when the sideline medical personnel don’t spot an injury,” Ingersoll says. “They’re good. But this position provides an added layer of observation and safety for the players.”

Ingersoll has access to the instant replay feed. But with his bird’s eye view, he also watches the game in real time, and communicates with the sideline when he sees an injury. At the Tulsa game this past Saturday, Ingersoll says, “I did not spot an injury that the sideline staff had not already seen.”

This is the first year that the AAC has enlisted a medical observer at UCF home games, Ingersoll says. But as the long-term consequences of brain trauma are better understood, the practice has been gaining support.

Football has come a long way in safety protocols since the NFL reached a more than $1 billion settlement in 2013 with retired players found to have long-term impacts of cognitive and neurological problems that stemmed from brain injuries sustained during their professional sports career.

The following year, fans watching a Michigan v. Rutgers football game booed when Shane Morris – who had sustained a hard hit to the head – was sent back in. Announcers observed that Morris could barely stand up.

Ingersoll not only has the academic knowledge to serve as a medical observer, but he also played football as an undergraduate at Marietta College in Ohio. As someone who has experienced and seen all kinds of injuries, he knows what he’s looking for – and concussive injuries are among the most serious that a player can experience.

“When you get hit in the head,” Ingersoll says, “The soft ball of jelly that is your brain gets bounced around in the hard shell of your brain. It disrupts the functioning of the cells in that part of your brain, either temporarily or permanently disrupting cell function.”

The AAC has policies regarding student athletes who are diagnosed with concussions, including not being allowed to return to play that day.

“You’re watching for someone who’s behaving abnormally after a hit,” Ingersoll says. “A player might show some balance deficit, often that can be pretty obvious. The goal is for the observer to pick that up and share with the sideline medical personnel.”

Collegiate football’s concern for the safety of its players has come a long way since its creation in 1869, Ingersoll says. Teddy Roosevelt, in particular, saved the game from its demise through urging head coaches in the Ivy League to curb excessive violence and pledge to keep the game clean.

From there, improvements in safety equipment and uniforms followed, the rules of the game continue to evolve, and the clinical knowledge of medical staff continues to be an integral part of game play.

“Today, there are more concerns than just winning a game,” Ingersoll says. “Having an extra set of eyes on player safety is a win for everyone.”