When Rachel Williams ‘96MA was growing up in Brevard County, her parents often urged her to consider a career in education. They were lifelong educators themselves, and knew their daughter possessed the traits of a great teacher. But Williams had other plans — to become a pediatrician. Now, Williams just laughs at how right her parents were. She is currently a full professor and the director of the Doctor of Speech-Language Pathology program at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale.

“I have had an interesting journey,” Williams says.

Though she started college with a very clear goal, Williams struggled with a required chemistry course as an undergraduate at the University of Florida. She didn’t love it as much as she thought she would. She knew her disinterest in the course probably did not bode well for her future career plans. Perhaps, she was not destined to become a physician.

So, her advisors suggested she take aptitude tests to determine where her true interests lay. Williams was surprised by the results – her first-tier results were all in education; her second-tier results were in allied health professions – which included speech-language pathology.

She learned that Speech-Language Pathologists (SLPs) could work with individuals of all ages, and that she could find employment in a school- or hospital-based setting, or even private practice.

Williams discovers her calling

Williams decided that she would become a pediatric SLP and work in a hospital because this would only be a small deviation from her original plan. As she neared the end of her undergraduate studies in communication sciences and disorders, she met Kenyatta Rivers, who was the first Black male doctoral student in speech-language pathology at UF.

“The other Black students and I were so happy to see him,” Williams says. At the time, she said it was rare to see any person of color in speech-language pathology, and especially to see them heading toward a doctoral degree in the profession.

After graduation, Williams moved back home to get a job, and to plot her course of action to attend graduate school.

Her parents fueled her determination to continue her education and become a professional. They wanted her to go as far as she could go.

She noticed that UCF was building a branch campus in Brevard County. She sought out Harold “Sonny” Utt, one of UCF’s communication sciences and disorders professors at that campus.

“I have never had a problem just walking up to people and talking to them,” Williams says. “I think I got that from my daddy, who had the gift of gab.”

Williams becomes one of UCF’s first Consortium students

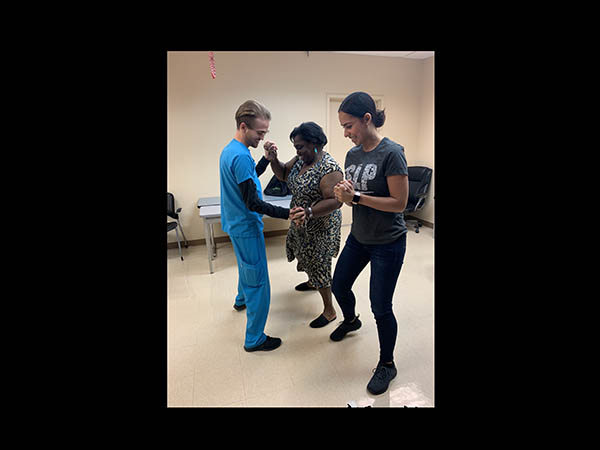

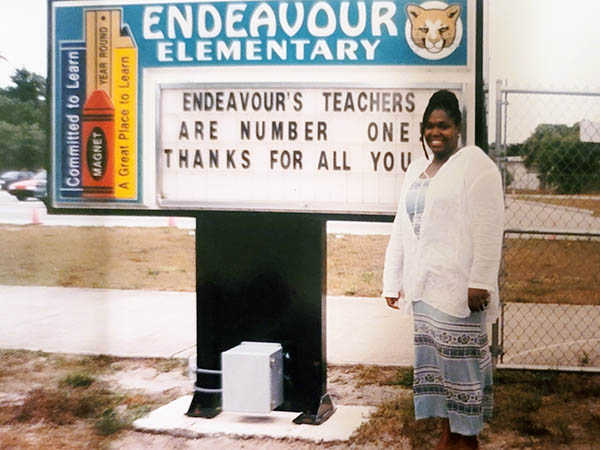

Utt told Williams about a new program that UCF had started to address the critical shortage of SLPs. Through the consortium program, Williams could work at a school in Brevard County, and attend classes at UCF. The classes were split between the Brevard and Orlando campuses. That all sounded good to Williams. So, she applied and was accepted to UCF as a graduate student to pursue her master’s degree in communication sciences and disorders. Much to the delight of her parents, Ralph and Shirley, she began working as an SLPA at a nearby elementary school. Back then, she says, they didn’t call them speech-language pathology assistants, but that’s what she was doing – working with kids on their communication skills.

At UCF, Williams also became a mentee of Linda I. Rosa-Lugo, who is the only Latina female faculty member in the department.

Rosa-Lugo inspired and supported Williams not only in the practice of speech-language pathology, but also in helping her encourage more diversity in the field. That impact has been long-lasting. Currently, Williams serves on ASHA’s Multicultural Issues Board, and she was elected as the first African American Florida Speech-Language-Hearing Association (FLASHA) president in 2011.

She also previously served as the former Chair for the National Black Association for Speech-Language and Hearing (NBASLH), which is the premier professional and scientific association addressing the communication interests and concerns of Black communication science and disorders professionals, students and consumers. She currently serves as the Chair of NSU’s Affiliate Chapter of NBASLH.

As Williams neared completion of the master’s program, she was surprised to see her old friend, Kenyatta Rivers, who had accepted a position at UCF after receiving his doctorate.

“We joked with each other,” Williams says. “’Are you following me, or am I following you?’”

Inspired by her late father, Williams begins pursuing doctoral degree

After receiving her master’s degree, Williams remained in Brevard County, and continued her position at her elementary school. She was happy to be finished with her master’s degree and truly enjoyed working with “her” kids. But her father kept encouraging her to push herself and achieve her full potential.

“My daddy always regretted not completing his doctorate degree,” Williams says. “He always told me to get as much knowledge as I can. Even after I had my master’s degree, he kept pushing me; he was afraid I would lose my passion for education and just let it slip by.”

It almost did slip by. When her father passed away unexpectedly in 1998, her mother continued to urge Williams to honor her father’s wishes and go back to school.

“I was hesitant at first,” Williams says. At the time, her mother had a chronic illness, and Williams was her caregiver. She was reluctant to leave her mother.

“My mother told me, ‘No, ma’am. You are not going to miss this opportunity.’”

Williams’ brother gladly stepped in to assist. And with his support and blessing, Williams forged on and was accepted into the doctoral program at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

As a doctoral student, Williams continued to work as an SLP in a public elementary school and continued asking the tough questions of her professors.

Williams was on the child-language track at Howard, but always had interest in fluency disorders. Of particular interest to her were the cultural myths associated with stuttering. “For example, one myth in Black culture is that if you cut a child’s hair before they learn to talk that it could cause stuttering,” Williams says. She connected with Tommy Robinson, Jr., adjunct faculty who had written a research article on myths found in stuttering for Blacks and was an expert in stuttering, to explore this further.

Additionally, she believed it was important for those in her profession and educational settings to understand the attitudes and beliefs associated with stuttering. She and Robinson determined that her dissertation research would explore attitudes and beliefs of middle and high school guidance counselors towards speech disorders (e.g. articulation, stuttering, and voice) and potential career choices for their students. “We were trying to capture where the seed is planted in these young children who stutter that could be limiting their potential as they determine their career or college path,” said Williams.

Also, with Robinson’s support, she earned a specialized certificate in stuttering along with her doctorate. She says while that was a very busy time in her life, she has learned to thrive in hectic environments.

“I have challenges every day,” Williams says. “Am I overwhelmed sometimes? Yes, absolutely. But I truly enjoy my students and helping in the community. Communication is such an important part of people’s lives.”

She has had many great mentors over the years, Williams said, but at the top of her list are UCF’s Sonny Utt, Kenyatta Rivers, and Linda I. Rosa-Lugo.

It is difficult for Williams to talk about her mentors Dr. Sonny Utt and Dr. Kenyatta Rivers, who both died recently. “I promised myself I wasn’t going to cry when I talked about them,” Williams said. But at every gathering she attends of ASHA, FLASHA and NBASLH, their names invariably make their way into the conversation.

“I am so grateful to UCF and to these three amazing individuals,” Williams says. “Their faith, guidance and support has shaped me into the person, SLP, and educator I am today.”